|

D4E-11094_800.jpg)

|

|

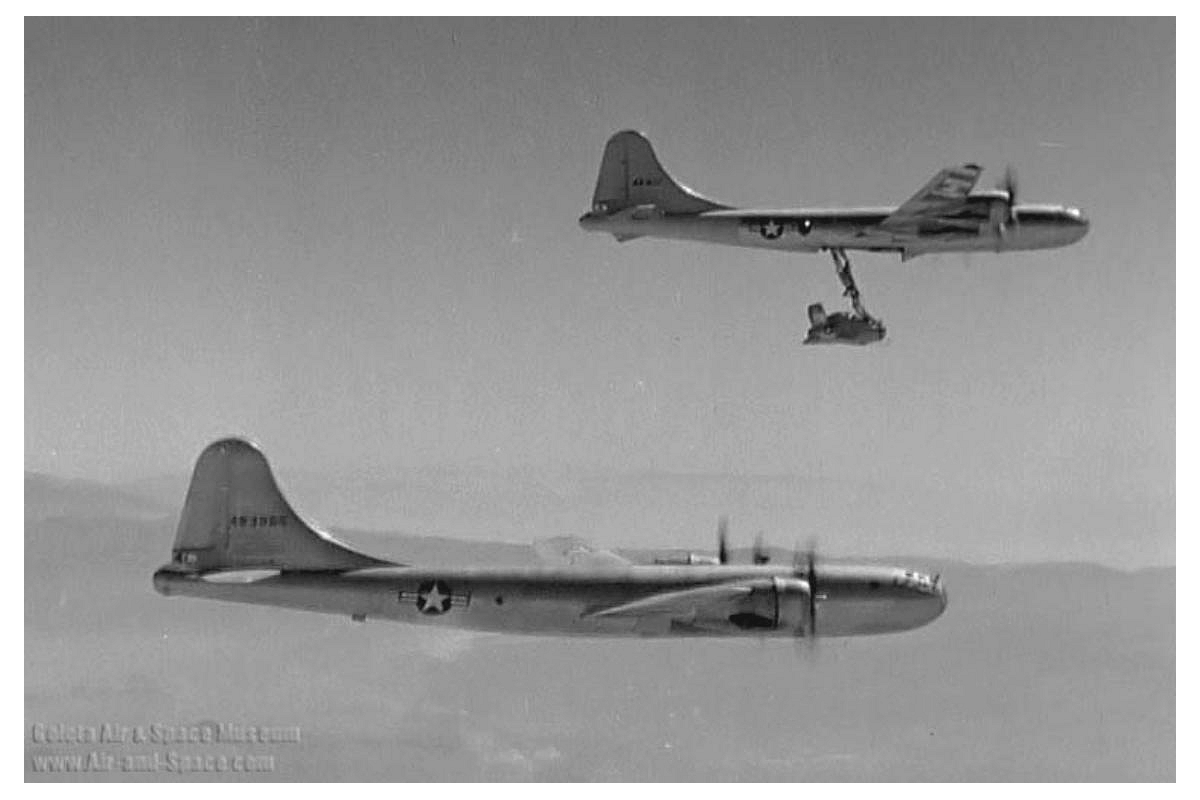

The XF-85 approaching the mother ship, EB-29B near the end of the first free flight, August 23, 1948, 20,000 feet above the Antelope Valley, California. A few seconds later the parasite struck and damaged the trapeze but did not hook on. Test Pilot Ed Schoch instead brought it to a landing on the dry lake bed below with its canopy broken. (Photo - McDonnell No. D4E-11094)

|

L'XF-85 si avvicina all'aereo madre, EB-29B verso la fine del primo volo libero, il 23 Agosto 1948, a 20.000 piedi sopra l'Antelope Valley, in California. Pochi secondi dopo, il parassita avrebbe colpito e danneggiato il trapezio, senza agganciarsi. Il pilota collaudatore Ed Schoch invece lo fece atterrare sul lago asciutto sottostante, con il canopy fracassato. (Foto - McDonnell No. D4E-11094)

|

RESEARCH PROJECT 7117 (Note: comment on the advancement of project 7117 are as of Fall 1973)

Research Project 7117 was begun more than three years ago by the Author to document the development of parasite-type aircraft, of which the McDonnell XF-85 Goblin was perhaps the most interesting. It had the most extensive program for development yet carried out by any agency, and during its course examined all of the avenues possible to extend the state of the art. Although never carried beyond the experimental stage, sufficient tests were made to determine that the concept was feasible.

Parasite aircraft are defined, for this discussion, as those designed to be launched from, and retrieved by, another aircraft in flight. The definition intentionally eliminates many configurations such as the World War I airplane/balloon experiments, the Fieseler Fi 103, and drone aircraft. The earlier efforts such as the British deHavilland Hummingbird experiments of 1925, the Russian efforts in the early 1930's, and the Curtiss Sparrowhawk/AKRON/MACON operations have been well documented.(1)

Richard D. Powers' review of parasite aircraft (RP7117) covers the three main concepts of the post-war era, all of which were American, and which included the Goblin, the wingtip coupling experiments, and the FICON project. This article is limited to the former. The author has in preparation articles on the US Air Force wingtip coupling and FICON operations, and would welcome the assistance of other Society Members having knowledge of these or other parasite aircraft projects.(2)

|

PROGETTO DI RICERCA 7117 (Nota: i commenti sullo stato di avanzamento del progetto 7117 si riferiscono all'Autunno 1973)

Il progetto di ricerca 7117 è stato avviato oltre tre anni fa dall'autore per documentare lo sviluppo di velivoli di tipo parassita, di cui il McDonnell XF-85 Goblin è forse stato il più interessante. Ha avuto il programma di sviluppo più esteso mai realizzato da qualsiasi agenzia governativa, e durante il suo corso ha esaminato tutte le strade possibili per estendere lo stato dell'arte. Sebbene non siano mai andati oltre la fase sperimentale, i test svolti sono stati sufficienti a determinare che il concetto era fattibile. Gli aerei parassiti sono definiti, ai fini di questa discussione, come quelli progettati per essere lanciati e recuperati da un altro aeeromobile in volo. La definizione elimina intenzionalmente molte configurazioni come gli esperimenti di aeroplani / palloni della prima guerra mondiale, i Fieseler Fi 103 e gli aerei telecomandati. Tentativi precedenti, come gli esperimenti britannici con il deHavilland Hummingbird del 1925, gli sforzi russi all'inizio degli anni '30 e le operazioni di Curtiss Sparrowhawk / AKRON / MACON sono già stati ben documentati. (1) La panoramica sugli aerei parassiti di Richard D. Powers (RP7117) copre i tre concetti principali dell'era postbellica, tutti americani, comprendenti il Goblin, gli esperimenti Wingtip Coupling di accoppiamento alare e il progetto FICON. Questo articolo si limita a affrontare il primo argomento. L'autore ha in preparazione articoli sulle operazioni con accoppiamento di estremità alare e FICON dell'Aeronautica USA, e riceverà con piacere l'assistenza di altri membri della Società che hanno conoscenza di questi o altri progetti di velivoli parassiti.(2)

|

|

The McDonnell XF-85 was conceived at the same time as the Convair XB-36, in the early World War Two years, when the possibility of isolation of United States armed forces to the North American continental limits became a viable concern of the Army Air Forces.(3) The parasite was intended to provide fighter protection for the new intercontinental bomber, and although the upper echelon leaders of the postwar Strategic Air Command came to have serious doubts of the usefulness of the XF-85 be-cause of its limited endurance, the project went forward and two research examples were built. Flight testing of the Goblin was limited to a series of seven flights over a period of eight months. Three successful hook-ons were made, and four flights terminated in belly landings on the dry lake bed at Muroc, California. The program was cancelled in April 1949 primarily because of difficulties in achieving successful retrievals with the trapeze skyhook.

Aircraft design has always been the art of compromise. In military aircraft, for instance, the requirements for long range and large payload usually resulted in large aircraft, while requirements for speed and manoeuvrability traditionally yielded smaller, light aircraft. Yet these mutually incompatible qualities were always necessary in at least two types, escort fighters and strategic reconnaissance airplanes. Escort fighters needed range comparable to the bombers they were protecting plus speed and manoeuvrability to successfully combat opposing interceptors. Recce types need the range to penetrate deeply into hostile territory and speed to elude the static and active defences.

Occasionally there have been attempts to use two aircraft with differing characteristics to accomplish the desired mission, rather than to combine elements into a single aircraft that would (hopefully) achieve the desired performance.

|

Il McDonnell XF-85 è stato concepito contemporaneamente al Convair XB-36, nei primi anni della Seconda Guerra Mondiale, quando la possibilità di un confinamento delle forze armate degli Stati Uniti nei limiti continentali nordamericani divenne una preoccupazione vitale per l'Army Air Force.(3) Il parassita era destinato a fornire un caccia di protezione per il nuovo bombardiere intercontinentale e, sebbene i leader di livello superiore del Comando aereo strategico del dopoguerra maturassero seri dubbi sull'utilità dell'XF-85 a causa della sua limitata autonomia, il progetto proseguì, e si costruirono due esemplari sperimentali. Le prove di volo (libero, NdT) del Goblin si limitarono a una serie di sette voli nell'arco di otto mesi. Si ottennero tre agganci riusciti, e quattro voli terminarono in atterraggi di pancia sul letto del lago asciutto di Muroc, in California. Il programma è stato cancellato nell'Aprile 1949 principalmente a causa delle difficoltà nel compiere agganci efficaci col sistema gancio ("skyhook") / trapezio.

La progettazione aeronautica è sempre stata l'arte del compromesso. Negli aeromobili militari, ad esempio, i requisiti di elevata autonomia e di elevato carico utile di solito si sono tradotti in aerei di grandi dimensioni, mentre i requisiti di velocità e manovrabilità hanno tradizionalmente prodotto velivoli più piccoli e leggeri. Eppure, queste qualità mutuamente esclusive sono sempre necessarie in almeno due tipi di aereo, caccia di scorta e aerei da ricognizione strategica. I caccia di scorta necessitano di un'autonomia paragonabile a quella dei bombardieri da proteggere, oltre che della velocità e della manovrabilità necessarie per combattere con successo gli intercettori avversari. Gli aerei da ricognizione hanno bisogno di autonomia per penetrare profondamente nel territorio ostile e della velocità necessaria per eludere le difese statiche e quelle attive.

Occasionalmente, si è tentato di utilizzare due velivoli con caratteristiche diverse per portare a termine la missione desiderata, piuttosto che combinare questi elementi in un singolo velivolo che (sperabilmente) raggiungesse le prestazioni desiderate.

|

|

Thus the parasite aircraft concept was born. The design objectives were met (in the case of the Curtiss F9C-2 and the McDonnell XF-85) by designing a small manoeuvrable aircraft that could be ferried to its operational area by a larger, long-range aircraft (the airships AKRON and MACON and the B-36). The fighters could be launched from the parent aircraft, complete the mission and return, be recovered and ferried back. This allowed each portion of the mission to be fulfilled by an aircraft that was nearly an optimum design. A price was paid for this improvement in efficiency; two aircraft were required to do the job of one, but further, the aerial launch and recovery techniques, upon which success depended, were extremely difficult to perfect, especially in less than ideal operational conditions.

The development of the McDonnell XF-85 Goblin parasite fighter really began on April 11, 1941.(4) On that date the Air Force issued a specification to industry calling for the design and development of an intercontinental bomber capable of carrying ten thousand pounds of bombs to targets five thousand miles away and returning, without refuelling, while cruising at speeds of 240-300mph.(5) The then current operational technique of daylight bomber operations was to send escort fighters along with the bombers to clear the air of opposing interceptors. The extreme range called for in this bomber specification created problems involving the escort that could be solved only by unconventional means. As aerial refuelling had not yet been perfected, the escort fighter would have to carry all its fuel internally or in drop tanks, but the amount of fuel required would dictate a fighter so large that it would be virtually useless against more nimble interceptors. A problem of equal magnitude was pilot fatigue; a round trip of ten thousand miles would require thirty hours to complete at 330 mph and fighter missions of this duration were beyond the capability of any pilot, particularly under combat conditions.

|

Così è nato il concetto di velivolo parassita. Gli obiettivi progettuali sono stati raggiunti (nel caso del Curtiss F9C-2 e del McDonnell XF-85) disegnando un piccolo aereo manovrabile che potesse essere trasportato alla sua area operativa da un aereo più grande a lungo raggio (rispettivamente, i dirigibili AKRON e MACON e il B-36). I caccia avrebbero potuto essere lanciati dall'aereo principale, completare la missione e tornare, essere recuperati e riportati indietro. Ciò avrebbe consentito di soddisfare ciascuna parte della missione con un aeromobile pressochè ottimale. C'era un costo da pagare per questo miglioramento dell'efficienza: servivano due velivoli per svolgere il lavoro di uno ma, oltretutto, le tecniche di lancio e recupero aereo da cui dipendeva il successo erano estremamente difficili da perfezionare, specialmente in condizioni operative non ideali.

Lo sviluppo del caccia parassita McDonnell XF-85 Goblin é davvero iniziato l'11 Aprile 1941.(4) In quella data, l'Air Force emise una specifica per l'industria che chiedeva la progettazione e lo sviluppo di un bombardiere intercontinentale capace di trasportare 4500 kg di bombe su bersagli a 8.000 km di distanza e di ritornare, senza rifornimento lungo il percorso, a velocità di 380-480 kmh.(5) La tecnica operativa allora corrente per le operazioni con i bombardieri diurni consisteva nell'inviare i caccia di scorta assieme ai bombardieri per liberare l'aria dagli intercettori avversari. Le distanze estreme richieste in questa specifica sui bombardieri crearono problemi relativi alla scorta, risolvibili solo con mezzi non convenzionali. Poiché il rifornimento in volo di carburante non era ancora stato perfezionato, il caccia di scorta avrebbe dovuto portare tutto il carburante internamente o in serbatoi esterni, ma la quantità di carburante necessaria avrebbe richiesto un caccia così grande, da essere praticamente inutile contro i ben più agili intercettori. Un problema di uguale entità era la stanchezza del pilota; un viaggio di andata e ritorno di diecimila miglia avrebbe richiesto trenta ore per essere completato a 530 km all'ora, e missioni di caccia di questa durata erano al di là della capacità di qualsiasi pilota, in particolare in condizioni di combattimento.

|

|

In December 1942 the Air Force initiated Project MX-472 for the purpose of solving this escort fighter problem. Preliminary studies included remotely controlled drones powered by ramjets, but by autumn 1944 these ideas were discarded in favour of a manned aircraft capable of being stored aboard the bomber.

Late in 1944, McDonnell Aircraft Company of St. Louis, Missouri, answered an Air Force Request for Proposal with four versions of its Model 27. No other company showed significant interest and McDonnell was awarded the contract. Initially, the Air Force planned to use the parasite fighter with the B-29, B-35, and B-36, externally hooked on. By January 1945, however, the decision had been made to design a fully retractable fighter, although this precluded its use with the B-29.(6) On October 9, 1945 a letter contract was signed by McDonnell and the Air Force covering Phase I - Engineering, for the project.

Model 27E, the McDonnell designation for the XF-85, emerged as a short, squat, low wing monoplane with an X-shaped tail and a sweptback folding wing, powered by a single Westinghouse turbo-jet engine. The final design, although unusual, was the most efficient configuration that would carry the necessary equipment and still fit inside the B-36 bomb bay.

The design problem has best been described hv Herman D. Barkey, the Project Engineer:

"The XF-85 was designed as a parasite fighter to be internally stowed in either the number one or the number four bomb bay of a B-36 and was therefore limited to an overall length of 15 feet and a stowed width of 5 ½ feet. The parasite carried normal fighter armament and was capable of being launched in one and one-half minutes at the cruising speed of the B-36 and retrieved at similar speeds while operating at an altitude of 35 to 40 thousand feet."(7)

|

Nel Dicembre del 1942 l'Air Force avviò il Progetto MX-472 allo scopo di risolvere questo problema dei caccia di scorta. Gli studi preliminari includevano droni telecomandati propulsi da statoreattori, ma nell'autunno del 1944 queste idee furono scartate a favore di un aereo con equipaggio capace di essere stivato a bordo del bombardiere.

Verso la fine del 1944, la McDonnell Aircraft Company di St. Louis, nel Missouri, rispose con quattro versioni del suo Modello 27 a una richiesta di proposte emessa dall'Aeronautica. Nessun'altra azienda mostrò un interesse significativo e la McDonnell ottenne il contratto. Inizialmente, l'Air Force ipotizzò di usare il caccia parassita con il B-29, il B-35 e il B-36, agganciato esternamente. Nel Gennaio del 1945, tuttavia, si prese la decisione di progettare un caccia completamente retraibile in fusoliera, anche se ciò ne avrebbe precluso l'utilizzo con il B-29. (6) Il 9 Ottobre 1945 McDonnell e USAF sottoscrissero un contratto a copertura della Fase I - Progettazione del progetto. Il modello 27E, la designazione McDonnell per l'XF-85, è emerso come un monoplano corto, tozzo, a ala bassa, con una coda a forma di X e un'ala ripiegabile a rotazione, alimentato da un unico turboreattore Westinghouse. Il progetto definitivo, anche se inusuale, era la configurazione più efficiente capace di portare l'attrezzatura necessaria e comunque di inserirsi all'interno della stiva bombe del B-36.

Il problema di progettazione è stato meglio descritto da Herman D. Barkey, l'ingegnere responsabile del progetto:

"L'XF-85 è stato progettato come un caccia parassita alloggiato internamente alla stiva bombe numero uno o numero quattro di un B-36 ed è stato quindi limitato ad una lunghezza complessiva di 4.5 m e una larghezza di 1.7 m. Il parassita trasportava normali armi da combattimento ed era in grado di essere lanciato in un minuto e mezzo alla velocità di crociera del B-36 e recuperato a simili velocità durante operazioni a un'altitudine di 10500 a 12200 metri".(7)

|

|

Goblin_cutaway_800.jpg)

|

|

Final accomplishment of this problem resulted in a configuration in which the fuselage was an aluminium alloy, semi-monocoque structure 14' 9" 3/4 long, with a maximum width of 50" and a maximum height of 79" 7/8. All equipment was housed in the fuselage to eliminate problems caused by folding the wings. The Westinghouse J-34-WE-22 turbojet was installed as far forward in the fuselage as possible to maximize the distance be-tween the aircraft center of gravity and the tail surfaces. A fifty-two-inch tailpipe extension carried the jet exhaust beyond the fuselage, with a special insulating blanket wrapped around to reduce heat transfer to the adjacent structure. Additional cooling was accomplished by diverting air from the intake duct around the engine and tail pipe.

Lubricating oil was contained in a five-gallon bladder type oil tank installed in the nose ring and fuel was contained in a single 115-gallon self-sealing, horseshoe-shaped tank located directly under the compressor section of the engine. An electric fuel pump, inside the tank, transferred fuel to the engine. The tank was kept cool by covering the tank wall nearest the engine compressor with heat-radiant material and by passing air between the compressor and tank.

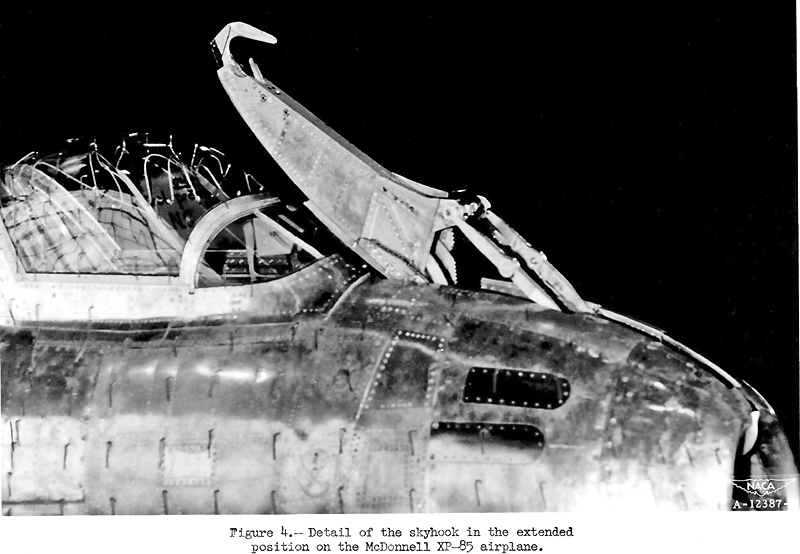

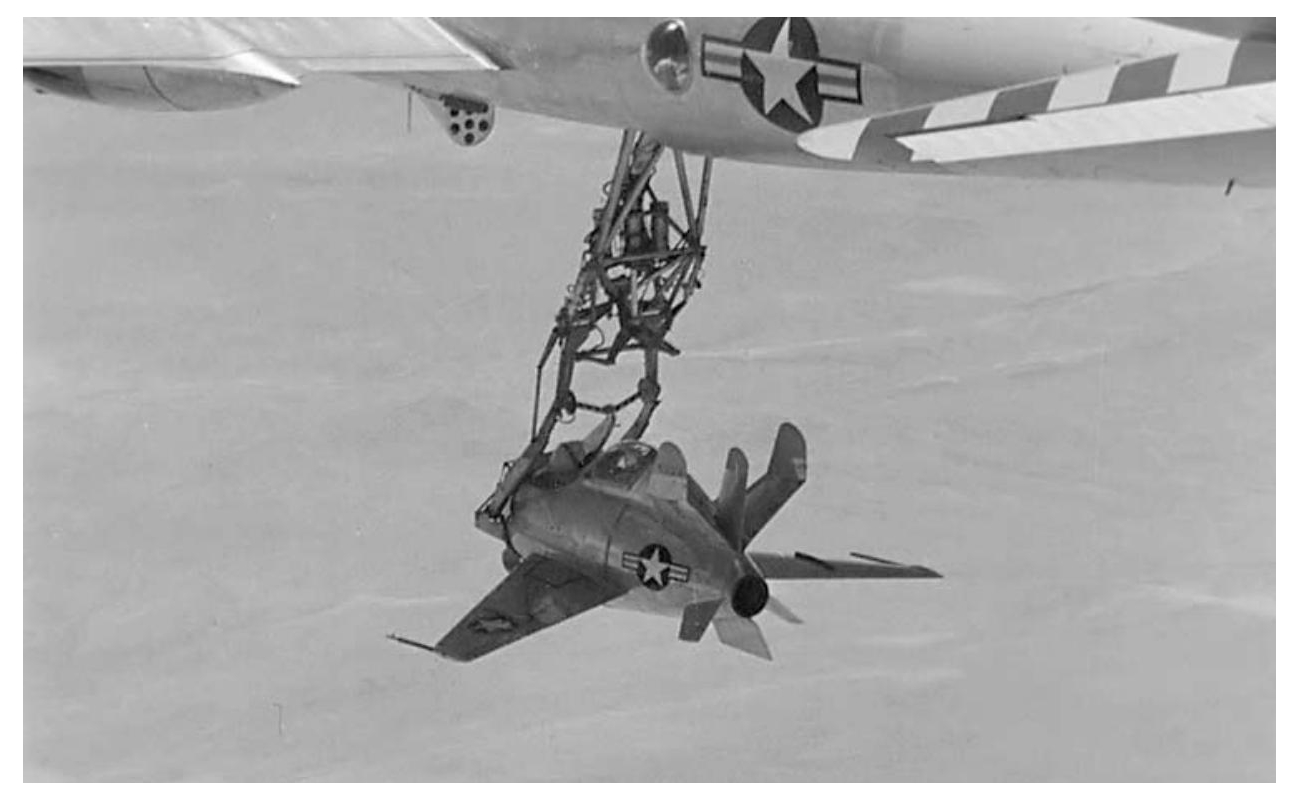

An electrically operated skyhook, located in the nose of the aircraft just ahead of the cockpit, was to link the parasite with the mother ship. Since there was little previous experience with parasite aircraft, this skyhook was designed on the same principle used by the Curtiss F9C-2 Sparrowhawk mechanism. It required a point of attachment above the fighter's center of gravity so the airplane could hang on the trapeze attached to the parent aircraft. In extended position, the XF-85's attachment point was two- to seven inches ahead of the center of gravity and about sixty inches above it. The parasite was to be released from the trapeze by tumbling the skyhook head. When the wings were folded, release was prevented by a safety switch, and if an electrical failure occurred, the skyhook could be retracted by a backup pneumatic system operating off the gun-chargers.

|

La soluzione finale di questo problema ha portato ad una configurazione in cui la fusoliera è una struttura semi-monoscocca in lega di alluminio, lunga 4.3 m, con una larghezza massima di 1.27 m e un'altezza massima di 2 m. L'equipaggiamento è alloggiato nella fusoliera per eliminare i problemi causati dal ripiegamento delle ali. Il turbogetto Westinghouse J-34-WE-22 è installato il più avanti possibile nella fusoliera per massimizzare la distanza tra il centro di gravità dell'aeromobile e la coda. Una prolunga di 1.3 m del condotto di scarico, contornata da uno speciale rivestimento isolante per ridurre il trasferimento di calore alla struttura adiacente, porta i prodotti di combustione del motore a getto oltre la fusoliera. Un ulteriore raffreddamento si otteneva deviando attorno al motore e al tubo di coda aria tratta dal condotto di aspirazione.

L'olio lubrificante era contenuto in un serbatoio flessibile da 22 litri, installato nella sezione anulare del muso, e il carburante era contenuto in un serbatoio autosigillante da 500 litri a forma di ferro di cavallo, situato direttamente sotto la sezione di compressione del motore. Una pompa di alimentazione elettrica, all'interno del serbatoio, trasferiva il carburante al motore. Il serbatoio era mantenuto fresco coprendo con materiale termoradiante la sua parete adiacente al compressore, e facendo passare aria tra il compressore e il serbatoio.

Un gancio ("skyhook") azionato elettricamente, situato nel muso dell'aereo immediatamente davanti al cockpit, avrebbe collegato il parassita all'aereo madre. Poiché l'esperienza pregressa con velivoli parassiti era scarsa, questo gancio venne progettato sullo stesso principio usato nel meccanismo del Curtiss F9C-2 Sparrowhawk. Era richiesto un punto di attacco sopra il centro di gravità del caccia, in modo che l'aereo potesse rimanere sospeso sul trapezio, attaccato all'aereo madre. In posizione estesa, il punto di attacco dell'XF-85 era da cinque a quindici cm più avanti del centro di gravità e circa 1.5 m sopra di esso. Il parassita doveva essere rilasciato dal trapezio facendo ruotare la testa del gancio. Ad ali ripiegate, il rilascio era impedito da un interruttore di sicurezza e, in caso di guasto elettrico, il gancio avrebbe potuto essere retratto da un sistema pneumatico di backup, lo stesso che azionava i caricatori delle mitragliatrici.

|

|

D4E-5289_800.jpg)

|

|

The XF-85 and B-36 mockup and the original trapeze configuration, at the McDonnell St. Louis plant on July 9, 1946, shortly after the mockup was reviewed by Air Force McDonnell and Convair representatives. (Photo McDonnell No. D4E-5289)

|

Il prototipo XF-85 e B-36 e la configurazione originale del trapezio, nello stabilimento di McDonnell St. Louis, il 9 Luglio 1946, poco dopo che il modello era stato esaminato dai rappresentanti dell'Air Force, di McDonnell e di Convair. (Foto McDonnell No. D4E-5289)

|

|

Armament was to consist of four .50 calibre type M-3 machine guns with 300 rounds of ammunition per gun. The ammunition was to be stored in a compartment just behind the cockpit, and the empty cartridges and links were to be ejected into an empty bay in the fuselage. The guns were aimed with a K-14 gunsight.

The cockpit of the XF-85 was about half the size of those in other fighters, with a volume of 26 cubic feet. The detail specification called for a pilot "not more than 5 feet 8 inches tall and weighing not more than 200 pounds when equipped with a para-chute and anti-g provisions."(8) The cockpit was pressurized by bleeding air from the engine compressor, passing this through a heat exchanger, a cooling turbine and a mixing valve which regulated the mixture of cool, pressurized air with hot air directly from the compressor. A pressure differential of 2.75 psi for normal operations or 1 psi for combat could be selected by the pilot. The escape system consisted of a T-4E powder charge fitted to the pilot's seat. Since the seat had to be placed directly over the engine, it was tilted back at an angle of thirty-three degrees from the vertical to reduce the frontal area of the aircraft. The small size of the cockpit meant that some unessential features had to be eliminated; for instance, rudder pedals were adjustable but the seat was not. Only a limited number of instruments could be provided:

- Radar beacon indicator

- Attitude gyro indicator

- Engine tachometer

- Turbine out temperature gauge

- Bearing temperature gauge

- Standby compass

- Airspeed indicator

- Airplane altimeter

- Cabin altimeter

- Accelerometer

- Gyro stabilized compass

- Fuel quantity gauge for main tank with low level warning light

- Fuel pressure gauge

The pilot was protected from the rear only, by a sheet of one-quarter inch thick steel for his head and shoulders, and a sheet of three-eighths inch thick aluminum alloy for his back. A two-piece canopy with a small, fixed windscreen and a sideward hinging hood was provided.

|

L'armamento doveva consistere in quattro mitragliatrici M-3 calibro 12.7 con 300 colpi per arma. Le munizioni erano riposte in un compartimento subito dietro l'abitacolo, e le cartucce e le maglie usate erano espulse in un compartimento vuoto nella fusoliera. Le mitragliatrici erano puntate grazie a un mirino K-14.

La cabina di guida dell'XF-85 era circa la metà di quella di altri caccia, con un volume di circa mezzo metro cubo. Le specifiche del dettaglio richiedevano un pilota "non più alto di 1.72 metri e di peso non superiore a 90 kg, già equipaggiato con un paracadute e tuta anti-g".(8) La cabina era pressurizzata con aria prelevata dal compressore del motore, passando attraverso uno scambiatore di calore, una turbina di raffreddamento e una valvola miscelatrice che regolavano la miscela di aria fredda e pressurizzata con aria calda proveniente direttamente dal compressore. Il pilota poteva selezionare un differenziale di pressione di 200 g/cm2 per le normali operazioni o di 70 g/cm2 per il combattimento. Il sistema di fuga consisteva in una carica di polvere T-4E montata sul sedile del pilota. Poiché il sedile doveva essere posizionato direttamente sul motore, era inclinato all'indietro con un angolo di trentatré gradi rispetto alla verticale per ridurre l'area frontale dell'aereo. Le piccole dimensioni dell'abitacolo comportavano l'eliminazione di alcune caratteristiche non essenziali; per esempio, i pedali del timone erano regolabili, ma il sedile no. Fu possibile fornire solo un numero limitato di strumenti:

- Indicatore radiofaro

- Indicatore del giroscopio di posizione

- Contagiri motore

- Indicatore della temperatura della turbina

- Indicatore della temperatura del cuscinetto

- Bussola di standby

- Indicatore della velocità

- Altimetro dell'aeroplano

- Altimetro della cabina

- Accelerometro

- Bussola girostabilizzata

- Indicatore della quantità di carburante per il serbatoio principale con spia di livello basso

- Manometro del carburante

Il pilota era protetto solo dal retro, da una lastra di acciaio spessa 6 mm per la testa e le spalle e da un foglio di lega di alluminio da circa 10 cm per la schiena. L'aereo era dotato di un canopy in due parti con un piccolo parabrezza fisso e un tettuccio fornito di cerniera laterale.

|

|

|

|

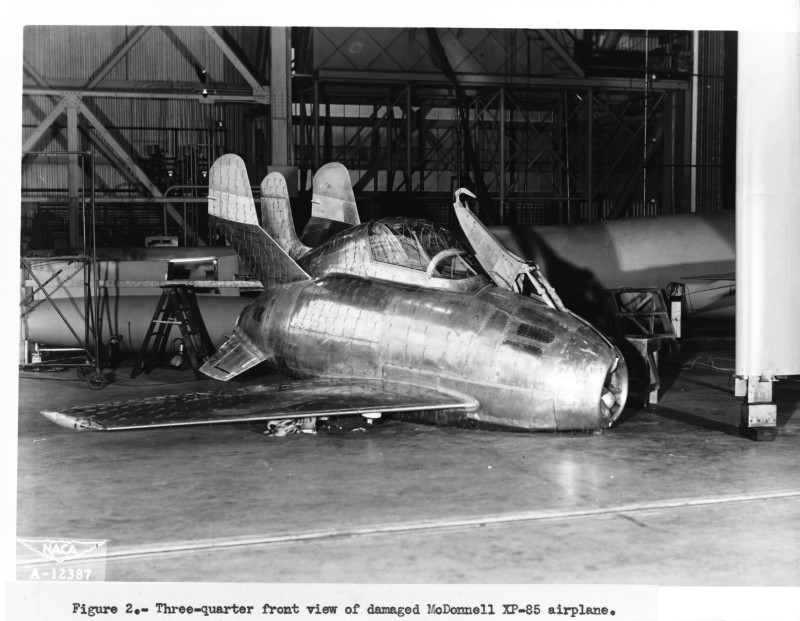

Detail of the extended skyhook (Photo-NACA A-12387 from the SA8I23 research memorandum, see link above)

|

Dettaglio dello "skyhook" esteso (Foto-NACA A-12387 dal memorandum di ricerca SA8I23, vedere link più sopra)

|

|

D4E-10112_800.jpg)

|

|

46-524, the second XF-85, in its initial configuration, May 1948, with sky-hook stowed. The wing stall fence is on the upper wing surface. The spring-steel wing skids, which were never used, are shown but not the center skid. (McDonnell No. D4E-10112)

|

Il secondo XF-85, 46-524, nella sua configurazione iniziale, nel Maggio 1948, con il gancio retratto. Il fence antistallo si trova sulla superficie dell'ala superiore. Sono mostrati i pattini a molla in acciaio, che non sono mai stati usati, ma non il pattino centrale. (McDonnell No. D4E-10112)

|

|

426A-G-4144BU_800.jpg)

|

|

Test Pilot Ed Schoch in the cockpit of 46-524 at Muroc. No flight tests had yet been made, the fairing around the base of the extended skyhook has been added, and the center skid is in place. (Photo-USAF, Edwards AFB No. 426A-G-4144BU, 15 July 1948.)

|

Il pilota collaudatore Ed Schoch nella cabina di guida del 46-524 a Muroc. Non sono stati ancora effettuati test in volo, è stata aggiunta la carenatura attorno alla base del gancio esteso, e il pattino centrale è al suo posto. (Foto-USAF, Edwards AFB No. 426A-G-4144BU, 15 Luglio 1948.)

|

|

A VHF communications transmitter and receiver (AN/ARC-5) and a radar beacon (AN/APN-61) were the only electronics equipment. Antennae for these were installed in the left and right vertical fin tips respectively, which were of a non-metallic construction.

All systems were electrically actuated, obviating the extra weight and fire hazard imposed by a hydraulic system. A small battery was provided for instruments, radio, and other small electrical equipment, and there were two external-power receptacles, one in the skyhook well for use when stowed aboard the parent aircraft and during the launch sequence, and another in the nose ring for use with an auxiliary power unit when testing on the ground.

The wings were fully cantilevered, of aluminium alloy stressed skin construction, designed to be folded and unfolded at the cruising speed of the B-36. For folding the wings, there were two hinges, one at each wing spar, with a locking pin at the main spar. The wingfold actuating circuit was incapable of operation unless the skyhook was extended. Nose flaps on the outer half of the wing leading edges extended automatically at speeds below 185 mph to improve lateral control.

An X-type tail, acting as both rudders and elevators, eliminated the need for a folding tail. The control surfaces acted as if the upper right and lower left surfaces were connected. Before flight testing began, dorsal and ventral fixed fins were added to improve directional stability.

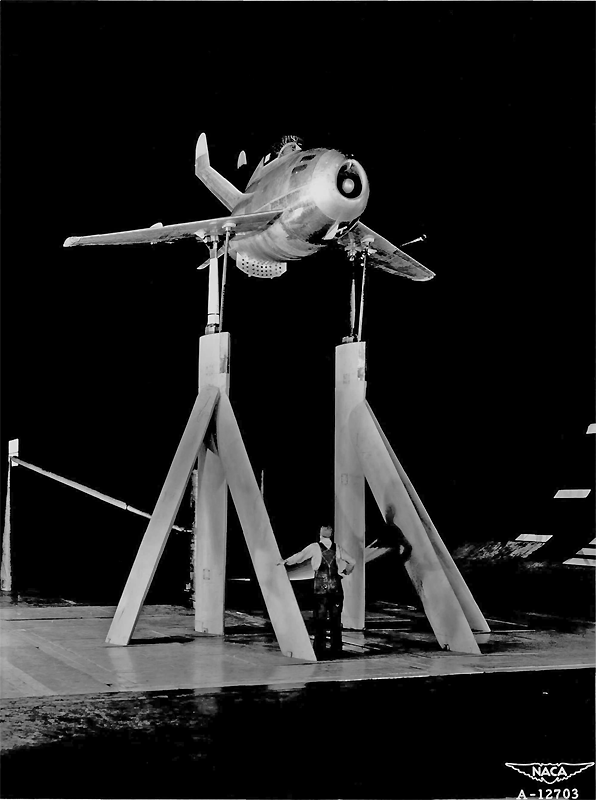

The hoe-type speedbrake, installed in the bottom of the fuselage, was manually controlled by a (momentary-type) toggle switch on the throttle grip, and provided accurate speed control, particularly during retrieving operations. The speedbrake also had an automatic mode, cued by a Mach switch, to limit the airspeed to the maximum controllable speed.

The landing gear originally considered for the flight test program was soon discarded. This type, a fixed tricycle landing gear, would double the XF-85's drag. A swivelling nose wheel was also considered but problems with wheel-shimmy eliminated this. The final arrangement consisted of a centerline main skid, which ex-tended ahead of the nose to prevent the aircraft nosing over, and two spring-steel skids located at mid-span on the wings to absorb the shock of a hard landing. The wing skids were removed prior to the first free flight and the center skid performed satisfactorily by itself, but at the request of the Air Force, runners were added to the wing tips to minimize damage caused by skid landings.(9)

|

Un trasmettitore e ricevitore di comunicazioni VHF (AN/ARC-5) e un radiofaro (AN/APN-61) erano le uniche apparecchiature elettroniche di bordo. Le relative antenne erano installate rispettivamente nelle estremità delle alette verticali sinistra e destra, che erano di materiale non metallico.

Tutti i sistemi erano azionati elettricamente, per evitare il peso aggiuntivo e il rischio di incendio insiti in un sistema idraulico. Era presente una piccola batteria per gli strumenti, la radio e altre piccole apparecchiature elettriche, e esistevano due prese di alimentazione esterna, una nel pozzetto del gancio, da usare quando l'aereo era stivato a bordo dell'aereo madre e durante la sequenza di lancio, l'altra nella sezione anulare del muso, da utilizzare con un'unità di alimentazione ausiliaria durante i test a terra.

Le ali erano completamente a sbalzo, in lega di alluminio rinforzato, progettate per essere ripiegate e dispiegata alla velocità di crociera del B-36. Per ripiegare le ali, c'erano due cerniere, una per ciascun longherone, con un perno di blocco sul longherone principale. Il circuito di comando del ripiegamento era disabilitato a meno che il gancio non fosse esteso. Le alette sulla metà esterna dei bordi anteriori delle ali si estendevano automaticamente a velocità inferiori a 300 kmh per migliorare il controllo laterale. Una coda ad X, con superfici agenti sia come timoni, sia come elevatori, eliminava la necessità di una coda ripiegabile. Le superfici di controllo agivano come se le superfici in alto a destra e in basso a sinistra fossero interconnesse. Prima dell'inizio delle prove di volo, furono aggiunte pinne fisse dorsali e ventrali per migliorare la stabilità direzionale.

L'aerofreno trapezoidale, installato nella parte inferiore della fusoliera, era controllato manualmente da un interruttore a levetta (di tipo momentaneo) sulla manetta del motore e consentiva un controllo accurato della velocità, in particolare durante le operazioni di recupero. L'aerofreno aveva anche una modalità automatica, comandata da un interruttore di Mach, per limitare la velocità indicata alla massima velocità controllabile.

Il carrello di atterraggio originariamente considerato per il programma di test di volo fu presto scartato. Tale carrello, fisso a triciclo, avrebbe raddoppiato la resistenza dell'XF-85. Si valutò anche l'adozione una ruota anteriore sterzabile, ma i possibili problemi di scuotimento della ruota ne suggerirono l'eliminazione. L'assetto finale é consistito in un pattino centrale, che si estendeva davanti al muso per evitare che il velivolo cappottasse, e due pattini a molla in acciaio situati a metà lunghezza sulle ali per assorbire gli urti di un atterraggio duro. Essi furono rimossi prima del primo volo libero, e il pattino centrale ha funzionato in modo soddisfacente da solo, ma su richiesta dell'Air Force, vennero aggiunte protezioni alle punte delle ali per minimizzare i danni causati dagli atterraggi ventrali.(9)

|

|

|

|

Number 2 XF-85, 46-524, with wings folded (Photo USAF via Goleta Air and Space Museum, USAF 17593r1 015706)

|

L'XF-85 Numero 2, 46-524, con le ali ripiegate (Foto USAF via Goleta Air and Space Museum, USAF 17593r1 015706)

|

|

After the Letter of Intent, a tentative order was placed for two XP-85 flight articles and one static test example, later augmented by a further 15 for service tests. The final letter contract, however, dated 18 June 1946, included only two stripped XF-85 parasite fighters, the definitive contract following on 2 February 1947. The stripped version had equipment essential only to its flight operation, plus some added to improve safety. The following changes were incorporated in the stripped version (as compared to the proposed design):

- guns were omitted;

- the dorsal fin was added;

- a manual override switch was provided to control the deflection of the leading edge flaps;

- only simulated armor was installed;

- the radar beacon was eliminated;

- a carbon-dioxide fire extinguisher was provided to spray CO2 around the engine burner section if overheating was detected;

- extra fuel tanks were provided, a 30-gallon integral tank in each wing and a 26-gallon bladder tank in the empty ammunition bay behind the cockpit;

- nitrogen pressurization was supplied to the extra tanks to force their fuel into the main tank, the only one equipped with a fuel pump.

During the second week of June 1946, from the tenth to the twelfth, representatives of the Air Force, Consolidated-Vultee, and McDonnell met in St. Louis to review the XF-85113-36 installation mockup. The proposed installation included provisions for heating the No. 1 bomb bay, storage for 2400 rounds of ammunition, refuelling equipment for the fighter (the XF-85 was to draw its fuel from the B-36's tanks), the trapeze and associated structure, and a decompression chamber. Estimates indicated that this equipment would add about 2200 pounds of weight to the B-36, not including the weight of the XF-85. The mockup was accepted as reviewed, except for a few minor modifications to the oxygen stations.

During the summer of 1947, while the basic engineering for the XF-85 was being completed, the first flight testing directly concerned with the program occurred. On July 22, McDonnell test pilot Robert Edholm and Air Force Major Kenneth Chilstrom flew Lockheed F-80's in simulated hook-on approaches to a B-29 near Wright-Patterson Air Force Base. The F-80s were flown with their dive brakes extended and forty percent landing flaps to simplify the job of keeping formation. The tests took place at twenty thousand feet and speeds of 180 and 225 mph. Four different types of approaches were flown, each with a different combination of speed and B-29 configuration, to evaluate the possible stability and control problems that might be encountered.

The first approach was flown with the B-29 at 225 mph and with the bomb bay doors closed. The F-80s approached from dead astern and reached a minimum distance from the B-29 of about six feet. Slight turbulence was encountered, but there was no problem in controlling the fighter airplanes. The second approach was similar to the first except that the bomb bay doors were opened. The F-80 pilots reported that they could feel the turbulence caused by vibration of the doors, but again no control problems were encountered. Next, the bomb bay doors remained open and the speed of the B-29 was decreased to 180 mph, but no change was noticed. The final approach was flown at 180 mph with the bomb bay doors open and the two inboard propellers feathered.

|

Dopo la lettera di intenti, è stato disposto un ordine provvisorio per due esemplari volanti dell'XP-85, e un esemplare per prove statiche, successivamente aumentato di altri 15 esemplari per i test di servizio. Tuttavia, la lettera di intenti definitiva, datata 18 Giugno 1946, copriva solo due caccia parassiti XF-85 non equipaggiati, con a seguire il contratto definitivo al 2 Febbraio 1947. La versione ordinata aveva solo l'equipaggiamento indispensabile per le operazioni di volo, più alcuni dispositivi aggiunti per migliorarne la sicurezza. Le seguenti modifiche rispetto al progetto proposto sono state incorporate nella versione a equipaggiamento ridotto:

- le mitragliatrici sono state omesse;

- la pinna dorsale è stata aggiunta;

- un interruttore di esclusione manuale è stato fornito per controllare la deflessione delle alette del bordo anteriore;

- è stata installata solo una corazzatura simulata;

- il faro radar è stato eliminato;

- è stato fornito un estintore a biossido di carbonio per spruzzare CO2 attorno alla sezione del bruciatore del motore in caso di surriscaldamento;

- sono stati forniti serbatoi di carburante extra, un serbatoio integrale da 135 l in ogni ala e un serbatoio flessibile da 520 l nel comparto delle munizioni vuoto dietro l'abitacolo;

- un sistema a azoto pressurizzato è stato aggiunto ai serbatoi supplementari per forzare il loro carburante nel serbatoio principale, l'unico dotato di una pompa del carburante.

Durante la seconda settimana di Giugno 1946, dal 10 al 12, i rappresentanti di Air Force, Consolidated-Vultee e McDonnell si sono incontrati a St. Louis per riesaminare il simulacro dell' installazione XF-85 / B-36. L'installazione proposta comprendeva i dispositivi per il riscaldamento della stiva bombe n. 1, l'immagazzinamento di 2400 munizioni, l'equipaggiamento di rifornimento per il caccia (l'XF-85 doveva prelevare il carburante dai serbatoi del B-36), il trapezio e la struttura associata, e una camera di decompressione. Le stime indicavano che questi dispositivi avrebbero aggiunto circa 1000 kg di peso al B-36, escluso il peso dell'XF-85. Il modello fu accettato come visto e piaciuto, tranne alcune piccole modifiche alle stazioni di presa dell'ossigeno.

Durante l'estate del 1947, mentre si stavano gettando le basi per la costruzione dell'XF-85, si svolsero i primi test in volo direttamente riferibili al programma. Il 22 Luglio, il pilota collaudatore della McDonnell, Robert Edholm, e il maggiore dell'aeronautica militare Kenneth Chilstrom, hanno volato con un Lockheed F-80 in approcci simulati di aggancio a un B-29 vicino alla Base Aerea Wright-Patterson. Gli F-80 volavano con gli aerofreni estesi e i flap di atterraggio al quaranta per cento per agevolare il mantenimento della formazione. I test hanno avuto luogo a 6000 metri e velocità di 290 e 360 kmh. Sono stati provati quattro diversi tipi di approccio, ognuno con una diversa combinazione di velocità e configurazione del B-29, per valutare i problemi di stabilità e controllo che si sarebbero potuti verificare.

Il primo approccio è stato effettuato con il B-29 a 360 kmh e con i portelloni della stiva bombe chiusi. Gli F-80 si sono avvicinati da poppa e hanno raggiunto una distanza minima dal B-29 di circa 1.8 m. Si è incontrata una leggera turbolenza, ma non si sono manifestati problemi nel controllo dei caccia. Il secondo approccio é stato simile al primo, tranne che per i portelloni della stiva bombe, che erano stati aperti. I piloti dell'F-80 riferirono che potevano percepire la turbolenza causata dalla vibrazione dei portelloni, ma neppure in questo caso si notarono problemi di controllo. Successivamente, i portelloni della stiva bombe sono rimasti aperti e la velocità del B-29 è stata ridotta a 290 kmh, ma non è stato notato alcun cambiamento. L'avvicinamento finale è stato effettuato a 290 kmh con i portelloni della stiva bombe aperti e le due eliche interne del B-29 in bandiera.

|

|

Goblin_drawing_800.jpg)

|

|

|

|

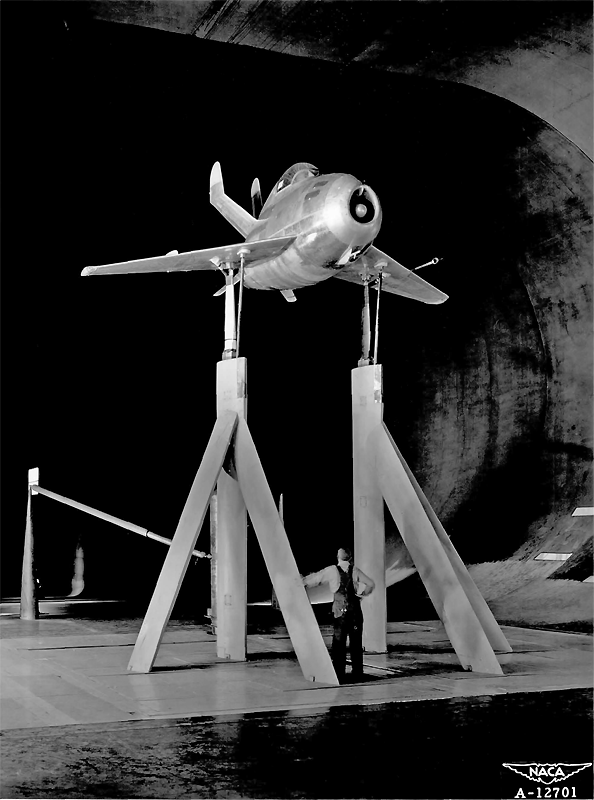

"INVESTIGATION OF THE MCDONNELL XP-85 AIRPLANE IN THE AMES 40- BY 80-FOOT WIND TUNNEL", Clean configuration (Skyhook and hoe-type speedbrake retracted) (Photo-NACA A-12701 from the SA8J22 research memorandum, see link above)

|

"INDAGINE SULL'AEREO MCDONNELL XP-85 NELLA GALLERIA DEL VENTO DI AMES DA 12 PER 24 METRI", Configurazione pulita (Skyhook e aerofreno trapezoidale retratti) (Foto-NACA A-12701 dal memorandum di ricerca SA8J22, vedere link più sopra)

|

|

|

|

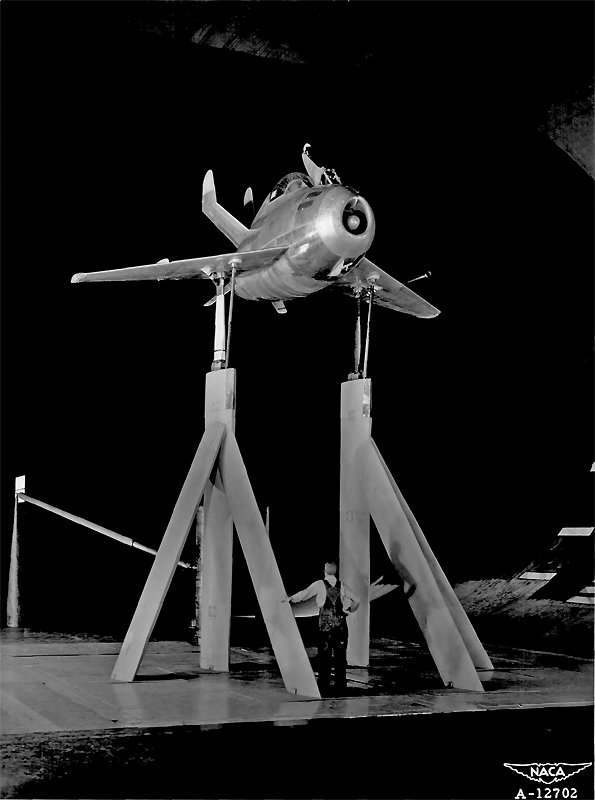

"INVESTIGATION OF THE MCDONNELL XP-85 AIRPLANE IN THE AMES 40- BY 80-FOOT WIND TUNNEL", Skyhook extended (Photo-NACA A-12702 from the SA8J22 research memorandum, see link above)

|

"INDAGINE SULL'AEREO MCDONNELL XP-85 NELLA GALLERIA DEL VENTO DI AMES DA 12 PER 24 METRI", Skyhook esteso (Foto-NACA A-12702 dal memorandum di ricerca SA8J22, vedere link più sopra)

|

|

|

|

"INVESTIGATION OF THE MCDONNELL XP-85 AIRPLANE IN THE AMES 40- BY 80-FOOT WIND TUNNEL", Hoe-type speedbrake extended (Photo-NACA A-12703 from the SA8I23 research memorandum, see link above)

|

"INDAGINE SULL'AEREO MCDONNELL XP-85 NELLA GALLERIA DEL VENTO DI AMES DA 12 PER 24 METRI", aerofreno trapezopidale esteso (Foto-NACA A-12703 dal memorandum di ricerca SA8I23, vedere link più sopra)

|

|

No great difficulty was experienced in approaching to within six feet of the bottom of the B-29, but the pilots recommended that the trapeze bar be placed at least ten feet below the bottom of the parent aircraft, out of the disturbed flow near the fuselage.

The unique configuration of the XF-85, caused by the size limitations of the B-36 bomb bay, made predicting the parasite fighter's aerodynamics difficult. Accordingly, the Air Force requested that the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics conduct wind tunnel tests on one of the airframes in the 40' x 80' tunnel at Ames Aeronautical Laboratory, Moffett Field, California.

The first airframe, 46-523, was completed in late 1947. Soon afterward, on Nov. 9th, the component parts, not including the engine, were crated and flown from St. Louis to Moffett Fd. in a C-97. November and December were spent in assembling the airframe and installing such special test equipment as control-surface hinge-moment gauges, pressure measuring systems, and remote control drives for the control surfaces. It was ready for installation in the tunnel on January 8, 1948.

Then the first mishap, that set the program back only a few days, occurred. It was decided to hoist the XF-85 into the test section by attaching the skyhook to a crane, a method felt to be safe since the airframe had been moved from the assembly area to the test area in this manner.

Late in the morning, the crane's cable was attached to the sky-hook and the XF-85 was lifted about three feet off the floor and bounced by hand to make sure the cable was secure. The attachment appeared to be safe, and when all swinging motion had ceased the airplane was slowly raised into the test section. The operation went smoothly until the XF-85 was about forty feet off the floor. Without warning, the hook latch slipped and the airplane fell. It struck the floor in a level attitude, crushing the forward part of the fuselage.

|

Non si è riscontrata alcuna difficoltà nell'avvicinarsi a meno di due metri dal fondo del B-29, ma i piloti hanno raccomandato di posizionare la barra del trapezio ad almeno tre metri sotto il ventre dell'aereo madre, fuori dal flusso disturbato vicino alla fusoliera.

La particolare configurazione dell'XF-85, causata dai limiti di dimensioni della stiva bombe del B-36, rendeva difficile prevedere l'aerodinamica del caccia parassita. Di conseguenza, l'Air Force ha chiesto al Comitato Consultivo Nazionale per l'Aeronautica (NACA) di condurre test su una delle cellule, nella galleria del vento di 12 x 24 m presso il laboratorio aeronautico Ames, a Moffett Field, California.

La prima cellula, 46-523, fu completata alla fine del 1947. Poco dopo, il 9 Novembre, i relativi componenti, escluso il motore, furono inscatolati e trasportati da St. Louis a Moffett Field, con un C-97. Novembre e Dicembre furono impiegati per assemblare la cellula e installare apparecchiature di prova speciali come misuratori di momento sulle cerniere delle superfici di controllo, sistemi di misurazione della pressione e unità di controllo remoto per le superfici di controllo. La cellula fu pronta per l'installazione nel tunnel l'8 Gennaio 1948. Fu allora che si verificò il primo contrattempo, che ritardò il programma solo per pochi giorni. Si era deciso di sollevare l'XF-85 nella sezione di test della galleria del vento, fissando il gancio a una gru, un metodo ritenuto sicuro poiché la struttura dell'aereo era stata spostata dall'area di assemblaggio all'area di prova in questo modo.

In tarda mattinata, il cavo della gru era stato collegato al gancio e l'XF-85 era stato sollevato a circa tre piedi dal pavimento e fatto oscillare a mano per assicurarsi che il cavo fosse sicuro. L'attacco sembrava tenere e, quando tutto il moto oscillante era cessato, l'aereo è stato lentamente sollevato nella sezione di test. L'operazione è andata a buon fine fino a quando l'XF-85 si è trovato a circa dodici metri da terra. Senza preavviso, il cappio è scivolato dal gancio e l'aereo è caduto. Ha colpito il pavimento in un assetto livellato, schiacciando la parte anteriore della fusoliera.

|

|

|

|

Number 1 XF-85, 46-523, slightly bent after its fall in the Ames Aero-nautical Laboratory test area while hoisting to the 40' x 80' wind tunnel. The skin was tufted to aid airflow visualization. (Photo NACA A-12387)

|

L'XF-85 Numero 1, 46-523, leggermente piegato dopo la sua caduta nell'area di test del Laboratorio Aeronautico di Ames mentre veniva sollevato nella galleria del vento 12 x 24 m. La superficie era stata ricoperta di filetti in tessuto per facilitare la visualizzazione del flusso d'aria. (Foto NACA A-12387)

|

|

A detailed inspection revealed that the nose section of the fuselage, the air inlet structure, and the primary and secondary structure of the fuselage had all sustained major damage and needed rebuilding. An investigating board later determined that the accident was caused by an improperly assembled latching mechanism which slipped under the weight of the XF-85.

The damaged airplane was returned to St. Louis and its place in the wind tunnel was taken by the remaining XF-85, serial number 46-524. Tests were completed early in 1948 and the data indicated that with the skyhook extended the directional stability of the airplane was decreased by 75 percent. It was recommended that a ventral fin be added to the configuration, bringing the number of tail surfaces to six. It was also noted, in disagreement with previous small-scale model wind tunnel tests, that the leading edge flaps were relatively ineffective.

Meanwhile, some doubts had been expressed as to the usefulness of the parasite fighter. In an article entitled "Parasite Jet Fighter Due for Test," Aviation Week reported(10):

"New Air Force contract for service test quantity of the P-85 (sic.-by this time the contract for two aircraft had been signed - Author) assures the unique craft a thorough wringing out at the hands of Air Material Command test pilots and indicates air force determination to exhaust the potentialities of the "parasite fighter" as a tactical concept in long-range bomber defensive armament. However, there are strong indications that the idea is slated for eventual abandonment.

"Gen. George C. Kenney, commanding general, U.S. Air Force Strategic Air Command, who will direct the tactical development and employment of the B-36A, is doubtful of the value the parasite fighter, because of difficulties of retrieving the planes after their small amount of fuel is used.

"If combat continues, the bomber which slows down to latch on a spent fighter is in jeopardy. It would be difficult for a fighter to find the "mother" plane which he had originally left and if he hooked on to another he would be taking the place of another parasite. With three fighters aboard the B-36A there is little if any space left for the stowage of bombs."

|

Un'ispezione dettagliata riveló che la sezione anteriore della fusoliera, la struttura della presa d'aria e la struttura primaria e secondaria della fusoliera avevano tutte subito danni rilevanti e dovevano essere ricostruite. Una commissione inquirente, in seguito, stabilì che l'incidente era stato causato da un meccanismo di aggancio montato in modo errato, che aveva ceduto sotto il peso dell'XF-85.

L'aereo danneggiato venne rispedito a St. Louis, e il suo posto nella galleria del vento fu preso dal rimanente XF-85, numero di serie 46-524. I test furono completati all'inizio del 1948 e i dati indicarono che con il gancio esteso la stabilità direzionale dell'aereo si riduceva del 75%. Si raccomandó di aggiungere una pinna ventrale alla configurazione, portando il numero di superfici della coda a sei. Si notó anche, in disaccordo con i precedenti test in galleria del vento su modelli a scala ridotta, che le alette sul bordo d'attaccco erano relativamente inefficaci.

Nel frattempo, erano stati espressi alcuni dubbi sull'utilità del caccia parassita. In un articolo intitolato "Il caccia parassita a getto in attesa di test", Aviation Week riportava(10):

"Il nuovo contratto dell'Air Force per la quantità di test di servizio del P-85 (Nota dell'autore: sic. - a questo punto, il contratto per due velivoli era stato firmato) assicura a questo velivolo, unico nel suo genere, un'accurato tartassamento per mano dei piloti collaudatori dell'Air Material Command, e mostra la determinazione dell'USAF ad esplorare nel modo più esauriente le potenzialità del "caccia parassita" come concetto tattico di armamento difensivo per bombardieri a lungo raggio. Tuttavia, esistono forti indicazioni che, in prospettiva, l'idea sia predestinata all'abbandono. Il Gen. George C. Kenney, comandante generale del Comando Aereo Strategico dell'Aeronautica USA, che dirigerà lo sviluppo tattico e l'impiego del B-36A, dubita del valore del caccia parassita, a causa delle difficoltà nel recuperare gli aerei dopo che la loro modesta quantità di carburante è é esaurita. Se il combattimento continua, il bombardiere che rallenta per agganciarsi a un caccia in riserva è in pericolo; sarebbe difficile per un caccia trovare proprio l'aereo madre che aveva originariamente lasciato e, se si agganciasse a un altro, avrebbe preso il posto di un altro parassita; con tre caccia a bordo del B-36A c'è poco spazio per caricare le bombe".

|

|

Unfortunately, Kenney's predictions would prove to be all too true, once flight tests were initiated.

The contract for the instrumentation and Phase I flight testing was signed in January, 1948. Phase I was a limited objective program, with the purpose of developing reliable hook-on procedures. From February 10th to 12th the Air Force Engineering Review Board met to evaluate the XF-85. Apparently the design was satisfactory, for no large modifications were recommended.

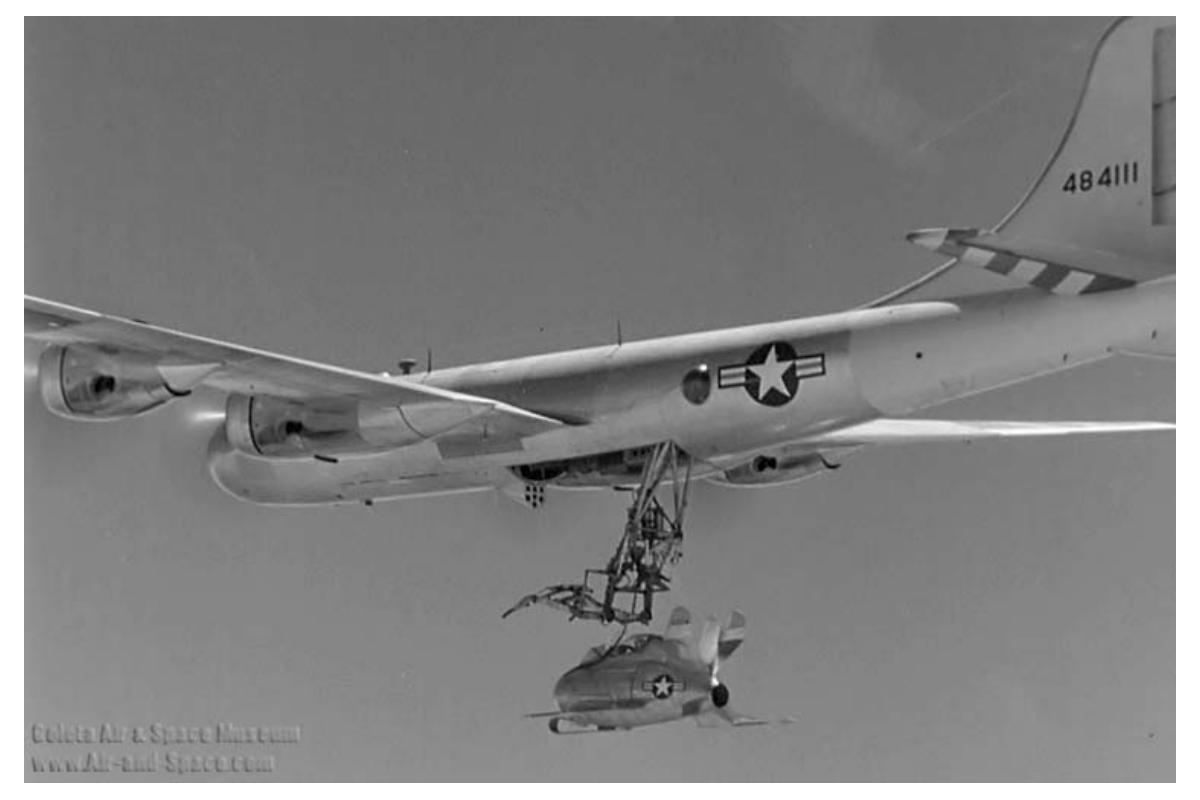

46-524 was brought back to St. Louis and, after two months of final preparation, it was flown to Muroc Air Force Base on June 5th in a C-97 to begin flight testing. Awaiting the XF-85 was the parent airplane for the program, an EB-29B, 44-84111, nick-named MONSTRO. The E prefix indicated that the B-29 was on bail to McDonnell.

It had become apparent, early in 1947, that no B-36 would be available for the flight test program, and a suitable substitute had to be found. A B-29 was the largest airplane readily available but the arresting trapeze had been designed for the B-36 and a new one had to be designed for the B-29. A letter contract supplement to the XF-85 contract was submitted in April, covering the B-29 modifications. The engineering for the modification was completed in October, and in January 1948 the definitive contract was signed.

The greater part of the modification was installation of the arresting trapeze, now placed in the aft bomb bay to keep the XF-85 away from the B-29's propeller discs. Keeping the AKRON-MACON experience in mind, McDonnell engineers designed the trapeze with the bar horizontal and with a "horse collar" stabilizing gear to grab the nose of the XF-85 thus holding it rigidly during retraction and extension.

|

Sfortunatamente, le previsioni di Kenney si sarebbero rivelate fin troppo veritiere, una volta avviate le prove in volo.

Il contratto per la strumentazione e le prove di volo di Fase I è stato firmato nel Gennaio del 1948. La fase I era un programma con obiettivi limitati, con lo scopo di sviluppare procedure di aggancio affidabili. Dal 10 al 12 Febbraio il Comitato di revisori dell'Aeronautica si riunì per valutare l'XF-85. Apparentemente il progetto venne ritenuto soddisfacente, dato che non vennero raccomandate grandi modifiche. Il 46-524 fu riportato a St. Louis e, dopo due mesi di preparazione finale, fu trasferito con un C-97 alla base aerea di Muroc il 5 Giugno, per iniziare i test in volo. A attendere l'XF-85, c'era l'aereo madre del programma, un EB-29B, 44-84111, denominato MONSTRO. Il prefisso E indicava che il B-29 era affidato, sotto cauzione, alla McDonnell.

Era apparso chiaro, all'inizio del 1947, che nessun B-36 sarebbe stato disponibile per il programma di test in volo, e che bisognava trovare un sostituto adeguato. Il B-29 era il più grande aereo disponibile, ma il trapezio d'arresto era stato progettato per il B-36 e bisonava progettarne uno nuovo per il B-29. Nel mese di Aprile è stato proposto un supplemento al contratto XF-85, a coprire le modifiche del B-29. Le attività ingegneristiche per la modifica furono completate in Ottobre, e nel Gennaio 1948 venne firmato il contratto definitivo.

La maggior parte delle modifiche è consistita nell'installazione del trapezio di arresto, ora collocato nella stiva bombe di poppa, per mantenere l'XF-85 lontano dai dischi dell'elica del B-29. Tenendo presente l'esperienza di AKRON-MACON, gli ingegneri della McDonnell progettarono il trapezio con una barra orizzontale e con un meccanismo stabilizzatore "a giogo" per afferrare il muso dell'XF-85 tenendolo rigidamente durante la retrazione e l'estensione. |

|

D4E-12062_800.jpg)

|

|

The cockpit of the XF-85 was cramped, only 26 cubic feet in size, with limited instrumentation. Central instruments were on the aft face of the skyhook well, others mounted on cockpit sides. From the photo immediately below, it's evident that this is an early stage of the assembly, with many instruments and controls still missing. (McDonnell D4E-12062)

|

La cabina di guida dell'XF-85 era angusta, di soli 500 litri circa, con strumentazione limitata. Gli strumenti centrali erano sul lato posteriore del pozzetto del gancio, altri erano montati ai lati del cockpit. Dalla foto immediatamente sottostante, è evidente che si tratta di uno stadio preliminare dell'assemblaggio, con molti strumenti e controlli ancora mancanti. (McDonnell D4E-12062)

|

|

|

|

A much better picture of the completed XF-85 cockpit taken on 18 August 1948, five days before the first flight. Photo courtesy of Ray Schoch (USAF, Edwards AFB No. 439B-G-4144BU)

|

Una foto molto migliore del cockpit dell'XF-85 completato, presa il 18 Agosto 1948, cinque giorni prima del primo volo. Foto gentilmente fornita da Ray Schoch (USAF, Edwards AFB No. 439B-G-4144BU)

|

|

In the extended position, the trapeze was located nearly 10 ½ feet below the bottom of the B-29, requiring a double hydraulic extension and retraction mechanism. A redundant emergency retraction system was installed to ensure that the trapeze could be pulled up, since the B-29 could not be landed with the trapeze extended. Other modifications to the EB-29 were:

- the bomb bay doors and bomb racks were removed;

- the tunnel in the rear bomb bay was removed;

- a fairing was installed ahead of the bomb bay to keep the free air stream from windmilling the XF-85's engine when stowed;

- radar equipment beneath the wing root was removed and the bomb bay extended forward thirty inches;

- protector plates for the fuel lines of the B-29 were installed;

- a CO2 fire extinguisher was installed under the wing root to inject its contents into the XF-85's engine if required;

- communications and oxygen outlets were installed.

The front bomb bay was used to house the emergency trapeze reservoir and emergency hydraulic pump. The aft pressurized compartment of the B-29 was converted to the control station for the trapeze by installing the trapeze control panel, a bench for the XF-85 pilot and mechanic, their oxygen and communication equipment.

The complex nature of the launch and recovery procedures required that the XF-85 pilot, the B-29 pilot, and trapeze operator be in contact at all times. These three crew members were therefore provided with a VHF radio system, all other crew members using the interphones. It was necessary to install an antenna for the VHF radio under the B-29 fuselage for use during launch and recovery. In all other flight modes the standard upper antenna was used.

An essential part of any flight test program is in-flight photography. Two 16mm cameras were installed on the B-29 for this purpose; one just ahead of the forward bomb bay below the fuselage, the other on the underside of the left wing, ahead of the aileron. Both pointed towards the trapeze bar, and streamline fairings minimized the drag of these cameras.

To ensure maximum visibility, a garish color scheme was now applied to MONSTRO. The entire aft end of the fuselage was painted yellow, and the wing tips and upper and lower surfaces of the horizontal stabilizer were painted with diagonal black and yellow stripes. The control surfaces were left in natural metal finish. In the early phases of the flight test program, as an additional visibility aid, the B-29 carried an M-16 smoke bomb, but this proved to be of little use. Although most of the free flights were performed in the vicinity of MONSTRO, visibility was constantly a factor which emphasized the need for a radar beacon in the operational aircraft. Had the program continued, smoke generating equipment similar to that used by skywriters was to be installed.(11)

|

Nella posizione estesa, il trapezio si trovava a circa tre metri sotto il fondo del B-29, e richiedeva un doppio meccanismo di estensione e retrazione idraulica. Venne installato un sistema ridondante di retrazione di emergenza, per garantire il sollevamento del trapezio, dato che il B-29 non poteva essere fatto atterrare con il trapezio esteso. Altre modifiche all'EB-29 sono state:

- i portelloni della stiva bombe e le rastrelliere delle bombe sono stati rimossi;

- il tunnel nella stiva bombe posteriore é stato rimosso;

- una carenatura è stata installata davanti alla stiva bombe per evitare che il flusso d'aria facesse girare passivamente il motore dell'XF-85 stivato;

- l'attrezzatura radar al di sotto della radice dell'ala é stata rimossa e la stiva bombe é stata estesa in avanti di trenta pollici;

- sono state installate piastre di protezione per le tubazioni del carburante del B-29;

- un estintore a CO2 è stato installato sotto la radice dell'ala per iniettare il suo contenuto nel motore dell'XF-85, se necessario;

- sono state installati i dispositivi di comunicazione e le prese dell'ossigeno.

La stiva bomba anteriore è stata utilizzata per alloggiare il serbatoio e la pompa idraulica del trapezio di emergenza. Il compartimento a poppa pressurizzato del B-29 è stato convertito a stazione di controllo per il trapezio, installando il relativo pannello di controllo, una panca per il pilota e il meccanico XF-85, il loro equipaggiamento per l'ossigeno e la comunicazione.

La natura complessa delle procedure di lancio e di recupero richiedeva che il pilota XF-85, il pilota B-29 e l'operatore del trapezio fossero sempre in contatto. Questi tre membri dell'equipaggio vennero quindi dotati di un sistema radio VHF, mentre tutti gli altri membri dell'equipaggio utilizzavano l'interfono. E' stato necessario installare un'antenna per la radio VHF sotto la fusoliera del B-29, da usare durante il lancio e il recupero. In tutte le altre modalità di volo si sarebbe utilizzata la normale antenna superiore.

Una parte essenziale di qualsiasi programma di collaudo è la fotografia in volo. A questo scopo sono state installate due telecamere 16mm sul B-29; una appena davanti alla stiva bombe anteriore sotto la fusoliera, l'altra sul lato inferiore dell'ala sinistra, davanti all'alettone. Entrambe puntavano verso la barra del trapezio e una carenatura riduceva al minimo la resistenza di queste telecamere.

Per garantire la massima visibilità, venne applicata a MONSTRO una combinazione di colori sgargiante. L'intera estremità poppiera della fusoliera venne dipinta di giallo, e le punte delle ali e le superfici superiore e inferiore dello stabilizzatore orizzontale vennero dipinte con strisce diagonali nere e gialle. Le superfici di controllo furono lasciate nella finitura in metallo naturale. Nelle prime fasi del programma di test in volo, come ulteriore ausilio alla visibilità, il B-29 portava una bomba fumogena M-16, ma ciò risultò essere di scarsa utilità. Sebbene la maggior parte dei voli liberi siano stati effettuati nelle vicinanze di MONSTRO, la visibilità è stata costantemente un fattore che ha sottolineato la necessità di un faro radar negli aerei operativi. Se il programma fosse proseguito, si sarebbe dovuto installare un sistema di generazione del fumo simile a quello usato dagli skywriter.(11)

|

|

D4E-10110_800.jpg)

|

|

The front view of 46-524 in May 1948 at the McDonnell St. Louis plant. The skyhook was retracted, and wing skids are in position. The port in the nose ring was for the gun camera. (D4E-10110)

|

Vista frontale del 46-524 nel Maggio 1948 nello stabilimento di McDonnell St. Louis. Lo skyhook è stato retratto e i pattini alari sono in posizione. La porta nella sezione anulare del muso era per la fotocamera delle mitragliatrici. (D4E-10110)

|

|

Another modification was extension of the B-29's tail skid to prevent the dragging of the XF-85 during takeoff. The length of the skid was doubled, and in even the retracted position it appeared much like a standard B-29 tail skid in the extended position.

The modifications were made by McDonnell at the St. Louis plant and the completed airplane was flown to Muroc by its McDonnell flight crew on Jan. 9, 1948, well ahead of the XF-85, to begin the flight test program. In its loaded condition, with 400 pounds of ballast in the nose compartment and 1396 pounds in the forward bomb bay, 4500 gallons of fuel, full complement of oil, eight crewmen and with the XF-85 installed, MONSTRO weighed 112,600 pounds. The corresponding landing weight was 101,800 pounds.

Since the EB-29B lacked sufficient clearance between the fuselage and the ground to permit loading the XF-85, a special loading pit was constructed at Muroc, 24 ½ feet wide, 92 feet long, and 17 ½ feet deep at one end. There was an inclined ramp permitting the XF-85 to be lowered on its ground handling dolly.

For the flight test operations, the EB-29B was to have three crewmen in the forward compartment and five in the aft, all McDonnell employees, chosen on the basis of their service experience and familiarity with the program. Albert W. Courtial was the pilot. A former Air Force captain, he had become familiar with the B-29 as pilot in the Pacific theatre during WWII. After the XF-85 tests he went on to New York to fly for the Bell Aircraft Corp. John Y. Brown was copilot, and he also had flown during WWII, in the Royal Canadian Air Force and the U.S. Navy.

The trapeze operator was Lester Eash, the engineer in charge of the B-29 modifications and the trapeze installation. The other crew members included Quinton Harvey, flight engineer, Keith Curtiss and D.P. Gadsby, mechanics, and Charles Siler, observer.

The only pilot ever to fly the XF-85 was Edwin F. Schoch, a McDonnell test pilot. Schoch, a graduate of Virginia Polytechnic Institute in 1941, enlisted in the Navy and was commissioned Ensign in April 1942. He joined the flight program and in 1943 was assigned to VF-19, flying Grumman F6F Hellcats off the USS LEXINGTON. He served with VF-19 for one tour of duty, claiming four Japanese airplanes destroyed and was awarded the Navy Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross, and the Air Medal. He was flying Corsairs aboard the USS LAKE CHAMPLAIN with VFB-150 when the war ended. Schoch then joined McDonnell as a test pilot, and thereafter flew nearly every type of airplane built by the company except the XP-67. He was killed on a test flight of an F2H-3 in September 1951.

|

Un'altra modifica è stata l'estensione del pattino di coda del B-29 per impedire il raschiamento dell'XF-85 durante il decollo. La lunghezza del pattino venne raddoppiata, e anche nella posizione retratta esso era comprabile a un pattino standard per B-29 nella posizione estesa.

Le modifiche furono apportate dalla McDonnell nello stabilimento di St. Louis, e l'aereo completato venne trasferito a Muroc dal suo equipaggio di volo McDonnell il 9 Gennaio 1948, molto prima dell'XF-85, per iniziare il programma di test in volo. Nella sua condizione di carico, con 180 kg di zavorra nel compartimento anteriore e 630 kg nella stiva bombe di prua, 20.000 litri di carburante, rifornimento completo di olio, otto membri dell'equipaggio e con l'XF-85 installato, MONSTRO pesava 51.000 kg.

Il peso corrispondente all'atterraggio era di 46.000 kg. Poiché l'EB-29B mancava di spazio sufficiente tra la fusoliera e il terreno per consentire il caricamento dell'XF-85, fu costruita una fossa di carico speciale a Muroc, larga 7.3 m, lunga 28 metri e profonda 5.3 a un'estremità. Una rampa inclinata permetteva di calarvi l'XF-85 sul suo carrello di movimentazione a terra.

Per le operazioni di test in volo, l'EB-29B doveva avere tre membri dell'equipaggio nel compartimento a prua e cinque a poppa, tutti dipendenti di McDonnell, scelti sulla base della loro esperienza di servizio e familiarità con il programma. Albert W. Courtial era il pilota. Ex capitano della Air Force, aveva familiarizzato con il B-29 come pilota nel teatro del Pacifico durante la seconda guerra mondiale. Dopo i test con l'XF-85 si trasferí a New York per volare per la Bell Aircraft Corp. John Y. Brown è stato il copilota, anche lui con esperienza di volo durante la seconda guerra mondiale, nella Royal Canadian Air Force e nella US Navy.

L'operatore del trapezio era Lester Eash, l'ingegnere incaricato delle modifiche del B-29 e dell'installazione del trapezio. Tra gli altri membri dell'equipaggio c'erano Quinton Harvey, ingegnere di volo, Keith Curtiss e D.P. Gadsby, meccanici e Charles Siler, osservatore.

L'unico pilota a volare sull'XF-85 è stato Edwin F. Schoch, un pilota collaudatore McDonnell. Schoch, diplomato al Virginia Polytechnic Institute nel 1941, si arruolò in Marina e fu nominato Guardamarina nell'Aprile del 1942. Si è iscritto al programma per divenire pilota, e nel 1943 è stato assegnato a VF-19, volando con i Grumman F6F Hellcat della USS LEXINGTON. Ha servito con il VF-19 per un ciclo di operazioni, abbattendo di quattro aerei giapponesi e venendo insignito di Navy Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross e Air Medal. Alla fine della guerra, stava pilotando Corsair a bordo della USS LAKE CHAMPLAIN con il VFB-150. Schoch si è poi impiegato alla McDonnell come pilota collaudatore, e da allora in poi ha volato praticamente su ogni tipo di aereo costruito dall'azienda eccetto l'XP-67. Ha perso la vita in un volo di collaudo di un F2H-3 nel Settembre del 1951.

|

|

The first tests in the program took place in June 1948 soon after the arrival of 46-524. As with any new airplane the flight test program was designed to progress in carefully planned steps to minimize the risks involved, and a series of preliminary ground tests were performed to check the performance of certain components. The power control, cooling and installation of the engine were checked, the magnetic compass was swung, and the cockpit was tested for carbon monoxide leaks.

Sufficient instrumentation to record all the important flight parameters was fitted. The flight test photo panel and a recording camera were installed in the empty ammunition bay in the fuselage behind the cockpit. (The 26-gallon bladder fuel tank was not used at this time because of the fire hazard.) Instrumentation was supplied to measure control surface positions, control forces, aircraft attitude and angular rotation, and the temperature of several structural members. Camera operation was to be controlled by Schoch.

The initial flight testing of the XF-85 consisted of captive flights during which the parasite was lowered into the airstream on the trapeze, the engine started, and the airplane "flown" while still hooked onto the trapeze. There was only enough freedom of movement to enable Schoch to get the "feel" of the controls. In all of these preliminaries, the engine, fuel, radio, and electrical systems were to be thoroughly checked out before clearing for free flight. Eleven captive flights were scattered throughout the flight test program; the first took place on July 22, 1948 and four others were made before the first free flight on August 23. Even these could be dangerous, as the following incident illustrates. The trapeze operator, Les Eash, at his station in the aft pressurized compartment between the gunner's blisters, had a good seat for the action. He recalled: "With the XF-85 on the arresting bar and the horse collar raised, the pilot started the engine and made repeated lift-offs within the confines of the hook diameter. The airplane was in control, moving laterally on the bar and pitching up and down. Subsequently, the airplane appeared to go divergent and Ed called for lowering the horse collar in an attempt to catch the oscillating nose. The first attempt I punctured the nose cowling and oil tank, the second missed completely and on the third attempt luckily caught the nose as it was moving in a lateral direction. After getting back to the ground, all I could say was, 'it was a helluva J.C.' "(12)

|

I primi test del programma si svolsero nel Giugno del 1948, poco dopo l'arrivo del 46-524. Come per ogni nuovo aereo, il programma di test in volo era progettato per progredire in fasi, attentamente pianificate per ridurre al minimo i rischi previsti, e ha compreso una serie di test preliminari a terra per verificare le prestazioni di specifici componenti. Il controllo della potenza, del raffreddamento e dell'installazione del motore sono stati testati, la bussola magnetica è stata collaudata e il cockpit è stato testato per eventuali perdite di monossido di carbonio.

E' stata montata una strumentazione sufficiente per registrare tutti i principali parametri di volo. Il pannello fotografico per i voli di prova e una telecamera di registrazione sono stati installati nel vano vuoto nella fusoliera dietro l'abitacolo. (Il serbatoio flessibile del combustibile da 120 litri non è stato usato in questa fase a causa del rischio di incendio). Sono stati forniti strumenti per misurare le posizioni delle superfici di controllo, le forze esercitate, l'assetto e la rotazione angolare dell'aeromobile e la temperatura di diversi componenti strutturali. Il funzionamento della videocamera doveva essere controllato da Schoch.

Il test in volo iniziale dell'XF-85 é consistito in voli vincolati, durante i quali il parassita, sul trapezio, veniva calato nella corrente d'aria, il motore veniva avviato e l'aereo "volava" ancora agganciato al trapezio. C'era una libertà di movimento appena sufficiente a consentire a Schoch di percepire il "feeling" dei comandi. In tutti questi preliminari, il motore, il carburante, la radio e i sistemi elettrici dovevano essere accuratamente controllati prima di essere abilitati per il volo autonomo. Undici voli vincolati sono stati effettuati durante il programma di test in volo; il primo ebbe luogo il 22 Luglio 1948 e altri quattro si svolsero prima del primo volo libero del 23 Agosto. Anche questi potevano essere pericolosi, come dimostra il seguente episodio. L'operatore del trapezio, Les Eash, nella sua postazione nel compartimento pressurizzato a poppa tra le cupole trasparenti dell'armiere, aveva un buon punto di vista sull'azione. Ha ricordato: "Con l'XF-85 sulla barra di arresto e il giogo sollevato, il pilota ha avviato il motore e fatto ripetuti decolli nei limiti del diametro del gancio. L'aereo era sotto controllo, muovendosi lateralmente sulla barra e facendo ripetuti su e giù. In seguito, l'aereo é parso divergere ed Ed ha chiesto di abbassare il giogo nel tentativo di catturare il muso che oscillava. Il primo tentativo ha bucato la cappottatura del muso e il serbatoio dell'olio, il secondo ha mancato completamente e il terzo ha fortunosamente afferrato il muso mentre si muoveva in direzione laterale. Dopo essere tornato a terra, potevo solamente dire 'E' stato un gran casino!'"(12)

|

|

2D4-4528_800.jpg)

|

|

The crew of the mother ship, MONSTRO. L.-R. – Albert Courtial, pilot; John V. Brown, co-pilot; Unknown; Jim McEwan, flight test engineer; Charles Siler, observer, and Les Eash, trapeze operator. (McDonnell No 2D4-4528.)

|

L'equipaggio dell'aereo madre, MONSTRO. Da sinistra a destra - Albert Courtial, pilota; John V. Brown, copilota; Sconosciuto; Jim McEwan, ingegnere per i test di volo; Charles Siler, osservatore, e Les Eash, operatore trapezio. (McDonnell No 2D4-4528.)

|

|

4E-12155_800.jpg)

|

|

MONSTRO and Goblin above the dry lake, now Edwards Air Force base, in October 1948 (probable date.) (McDonnell No. 4E-12155)

|

MONSTRO e Goblin sopra il lago asciutto, ora base delle Forze Aeree di Edwards, nell'Ottobre del 1948 (data probabile). (McDonnell n. 4E-12155)

|

|

The sequence of events on all flight operations was similar: The XF-85 was installed on the trapeze in the loading pit and the trapeze retraction mechanism was tested on both primary and emergency systems.

Schoch rode in the aft compartment of the B-29 during take-off. After launch altitude was reached, the XF-85 was partially lowered and, after Schoch entered the bomb bay, it was again retracted. After climbing into the cockpit, Schoch would give a signal for the parasite to be lowered. Once the parasite was lowered, the engine was started, the horse collar was raised, and the launch completed.

To maintain his proficiency during the flight testing, Schoch flew simulated approaches to the EB-29B in an F-80, forty approaches during the course of fourteen flights. For these, a simulated skyhook similar to an automobile radio antenna was installed just ahead of the cockpit, approximating the position of the XF-85's hook. In general, the two types of aircraft required similar techniques for the approach, though the difference in sizes made the handling quite different. Two chase airplanes were used, a Lockheed F-80 to follow the XF-85, and a B-29 to observe and photograph the launch and recovery procedures.

|

La sequenza di eventi era simile in tutte le operazioni di volo: nella fossa di carico, l'XF-85 veniva installato sul trapezio, e il meccanismo di retrazione del trapezio veniva testato su entrambi i sistemi, primario e di emergenza.

Schoch sedeva nel compartimento poppiero del B-29 durante il decollo. Dopo aver raggiunto l'altitudine di lancio, l'XF-85 veniva parzialmente abbassato e, dopo che Schoch era entrato nella stiva bombe, veniva di nuovo ritirato. Dopo essere entrato nel cockpit, Schoch dava un segnale per calare il parassita. Una volta che il parassita era stato calato, si avviava il motore, si sollevava il giogo e si completava il lancio.

Per mantenere la sua efficienza durante i test in volo, Schoch, in un F-80, ha eseguito approcci simulati all'EB-29B, quaranta approcci nel corso di quattordici voli. In questi voli, un simulatore di gancio simile ad un'antenna radio per automobili era stato installato poco più avanti del cockpit dell'F-80, approssimando la posizione del gancio dell'XF-85. In generale, i due tipi di aeromobili richiedevano tecniche simili per l'approccio, sebbene la differenza di dimensioni rendesse la manovra abbastanza diversa. Sono stati usati due "chase planes", un Lockheed F-80 per seguire l'XF-85 e un B-29 per osservare e fotografare le procedure di lancio e di recupero.

|

|

The flight characteristics of MONSTRO with the XF-85 in the stowed position were not much different from a standard combat B-29. With the trapeze extended, the airspeed dropped about forty miles per hour. Maintaining the launch speed of 200 mph required slightly more power than the maximum continuous rating. When the XF-85 was launched, a very slight nose down tendency required the application of a small amount of up elevator. Only a slight reduction of engine manifold pressure was possible after launch, if 200 mph was to be maintained.

The first XF-85 free flight in 46-524 was made on August 23, 1948. The launch was made at 20,000 feet and 200 mph. After the engine was started and the horse collar raised, Schoch pulled the lever that tumbled the skyhook head and gently pulled back on the stick to ease the initial rate of descent. The parasite dived away with no problems. After a brief period spent feeling out the controls for the first time in free flight, Schoch performed a preliminary evaluation of the XF-85's flight characteristics through the speed range from 180 to 250 mph. He judged that it had excellent lateral stability and control, positive directional stability and control, and satisfactory longitudinal stability and control, but insufficient trim capability required him to exert a constant pull of 10 to 50 pounds on the stick in order to maintain level flight.

|